What is meant by the term Organisational Culture?

As experienced coaches, mentors, and teachers, we seek to promote greater understanding of the contemporary issues surrounding Organisational Culture (OC).

OC is just one way of describing a business. It has been defined as the visible and less visible norms, values and behaviours, that are shared by a group of employees, which shape the group's sense of what is acceptable and valid. These are generally slow to change, and new group members learn them through both an informal and formal socialisation process. (Wilson, A. 2001)

Since the 1990’s, Edgar Schein has been considered as one of the foremost experts in the study of OC. To really understand a culture and to ascertain more completely the group’s values and overt behaviour, it is imperative to delve into the underlying assumptions, which are typically unconscious, but which actually determine how group members perceive, think, and feel’ (Schein, 1985, p. 3). Schein describes the development of culture as the most important job of a leader. He says:

The objective of developing good organisational culture is to have your people to reliably behave how you want in your absence by getting them to think how you want.

This highlights the importance of getting all employees to understand, accept, adopt, and operate in ways that you have built your organisation, (through practices, systems, and processes), adopted, and modelled the organisations values in the way that you behave. This places great responsibility on all employees, not just the appointed leaders. He suggested three cognitive levels of analysis can create a better understanding of the different components of culture in organisations: artefacts, values and beliefs, and basic assumptions.

Artefacts: things seen on the surface, visible to the observer such as office design, furniture, rewards and credits, the dress code, and the visible interaction between employees themselves and other stakeholders.

Explicit values and beliefs. Stated, published, espoused. This includes the expression of the mission statement, strategies, goals, philosophies, and the functioning beliefs throughout the organisation.

Schein believes that experiencing and overcoming problems as a group/team results in the evolution of a pattern of basic assumptions, invented, discovered, or developed by the group as it learns to cope with its problems of external adaptation and internal integration. If these adaptations work well enough, they are considered to be valid and therefore to be taught to new members as the correct way to perceive, think and relate to those problems (Schein, 1991, p. 9). Schein believed that these were evident in behaviours, and easily identifiable.

Some have criticised his work for not including the implicit and unspoken rules that employees are not consciously aware of, but which are deep rooted and may provide an explanation to understanding why things take place in a particular way. These are the deeply held, but possibly (unconsciously) hidden, basic assumptions. The critical element is for these collections of fundamental assumptions to be shared and accepted by organisational members. Smircich (1983) makes a particularly poignant point that culture evolves. This opens the door to the concept of change. ‘All experts agree that no company has ever delivered a monoculture successfully’. (Martin (2002)

Why does a leader need to be aware of organisational culture?

Understanding organisational culture is seen as important in several areas of the management literature including organisational behaviour, change management, and strategy implementation (Foster and MacDonald, 2013).

In an era of emotional intelligence, where leaders are expected to be aware of the needs of their employee’s, clients, and stakeholders, an understanding of the different categories or classifications of organisational culture, realising the impact of each typology, and accepting that change is required for growth and survival as a business and/or a leader of people, is absolutely essential.

A consultant that espouses to work in the area of organisational development must be able to explain contemporary understanding of organisational culture, and educate leaders and followers to recognise the reality of where they are, and where they would like to be.

Contemporary understanding of Organisational Culture

There have been many definitions of what organisational culture means, but probably the simplest, and most understandable is:

The way we do things around here. (Bower, 1966)

Martin (1992), posited that there are three distinct social science approaches to studying OC. An integration approach which centres on that which is shared by all members of an organization; a differentiation view which is founded on the notion that each organisation may have a series of ‘tribes’ within it, (which can lead to sub-cultures) each holding different cultural tenets; and a fragmentation view which centres on ambiguity and inconsistencies in organisational practices and perspectives as a way of articulating organisational culture (Foster and MacDonald, 2013).

The work of Johnson and Scholes takes an integrative approach, summarizing the various ‘basics’ that describe the culture of organizations (Johnson, 2000.) An Integration view of culture research takes the view that culture is understood through the study of all that is common or agreed within the organisation. This set of characteristics is commonly used in studying OC, and is shown below as a cultural web:

Other approaches seek to classify OC into typologies by using observations to identify the dominant culture. For example, the work of Deal and Kennedy emanated from academic research into a new powerhouse in the business world after WWII, Japan. They discovered that intrinsic motivations outweighed extrinsic motivations for the highest performing businesses, by considering two key dimensions, the degree of risk associated with the company’s activities, and the speed at which companies – and their employees – get feedback on whether decisions or strategies are successful. The four typologies identified are: tough guy/macho culture, bet-your-company culture, work hard/play hard culture, and process culture.

Does your organisation fall into one of these typologies?

1. The tough guy, macho culture

A world of individualists who regularly take high risks and get quick feedback on whether their actions were right or wrong. These cultures are characterised by aggressive internal competition. This type of culture is commonly thought to be prevalent in organisations in which feedback comes in the form of financial rewards. Managers in this type of culture need to be able to make decisions quickly and to accept risk. To survive when things go wrong, they need to be resilient. Innovation would be very difficult to achieve in such an environment if results were expected in the short-term.

2. The work hard/play hard culture.

Fun and action are the rule here, and employees take few risks, all with quick feedback; to succeed, the culture encourages them to maintain a high level of relatively low-risk activity. They are typical of large organisations such as the motor industry, IT and telecoms because in smaller organisations there are often increased levels of risk as ‘every decision is a big one’. The high levels of energy create two main problems for a manager: ensuring that the energy is being directed at the right tasks and ensuring that quality accompanies the high levels of activity.

3. The bet-your-company culture.

Cultures with big-stakes decisions, where years pass before employees know whether decisions have paid off. A high-risk, slow-feedback environment. This type of culture is found in organisations involved in projects that consume large amounts of resources and take a long time to be realised. Each of these projects is very risky and the organisation does everything it can to ensure it makes the right decisions initially.

4. The process culture.

A world of little or no feedback where employees find it hard to measure what they do; instead, they concentrate on how it’s done. Employees in these cultures may be very defensive. They fear and assume that they will be attacked when they have done things incorrectly. This is highly bureaucratic environment.

Or does your organisation fall into one of the four types of Organisational Culture posited by Charles Handy (1989)?

a. The Power Culture

Organisations with this type of culture can respond quickly to events, but they are heavily dependent for their continued success on the abilities of the people at the centre; succession is a critical issue. They will tend to attract people who are power orientated and politically minded, who take risks and do not rate security highly. Control of resources is the main power base in this culture, with some elements of personal power at the centre.

b. The Role Culture

This type of organisation is characterised by strong functional or specialised areas coordinated by a narrow band of senior management at the top and a high degree of formalisation and standardisation; the work of the functional areas and the interactions between them are controlled by rules and procedures defining the job, the authority that goes with it, the mode of communication and the settlement of disputes. In such organisation’s technical expertise and depth of specialisation are more important than product innovation.

c. The Task Culture

Task cultures are often associated with organisations that adopt matrix or project-based structural designs. The emphasis is on getting the job done, and the culture seeks to bring together the appropriate resources and the right people at the right level in order to assemble the relevant resources for the completion of a particular project. A task culture depends on the unifying power of the group to improve efficiency and to help the individual identify with the objectives of the organisation. It is a team culture, where the outcome of the team’s work takes precedence over individual objectives and most status and style differences.

d. The Person Culture

Person culture is quite unusual and reflects organisations in which individuals believe themselves to be superior to the organisation. For this reason, employees tend to be transient. Specialists in organisations, such as computer people in a business organisation, consultants in a hospital, architects in local government and university teachers benefit from the power of their professions. Not many organisations can exist as a Person Culture, or produce it, since organisations tend to have some form of corporate objective over and above the personal objectives of those who comprise them. Furthermore, control mechanisms, and even management hierarchies, are impossible in these cultures except by mutual consent. This type of culture may well be conducive to innovation, but employees require very careful skilful management in order to maintain a focus on the organisation’s overall objectives.

Measuring Organisational Culture

There are many more ways to define OC, each is, however, limited by the findings and opinion of the author of such definitions or models. As the reader, you are probably asking; What if none of them adequately describes our OC or even our desired OC?

You may also be asking, What if we have elements of two or more? If so, perhaps one of the most used tools is the Organisational Culture Assessment Instrument (OCAI) from Cameron and Quinn (1999).

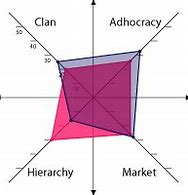

Kim Cameron and Robert Quinn (1999) conducted research on organisational effectiveness and success. Based on the Competing Values Framework (CVF), they developed the OCAI that distinguishes four culture types dependent on: (a) the degree of flexibility, (b) the amount of stability and control, (c) the focus of internal and external forces in terms of the socialisation, and (d) the amount of integration or differentiation in the way people interact.

“The CVF is one of the most influential and extensively used models in the area of organisational culture research. (Kwan and Walker. 2004). Competing values produce polarities (opposites) like flexibility v stability, and internal v external focus – these two polarities were found to be most important in defining organisational success. The polarities construct a quadrant with four types of culture:

Clan culture (internal focus and flexible) – A friendly workplace where leaders act like father figures.

Adhocracy culture (external focus and flexible) – A dynamic workplace with leaders that stimulate innovation.

Market culture (external focus and controlled) – A competitive workplace with leaders like hard drivers.

Hierarchy culture (internal focus and controlled) – A structured and formalized workplace where leaders act like coordinators.

Cameron and Quinn believe that every organisation has its own combination of these four types of organisational cultures. They designated six characteristics of organisational culture that can be assessed with the Organisational Culture Assessment Instrument (OCAI). This method determines the blend of the four culture types that dominate the current organisational or team culture. The OCAI is completed twice but from different perspectives, firstly, how one see’s the organisation (reality), and secondly from how one would like the organisation to be.

From Cameron and Quinn’s extensive study, it was found that most organisations have developed a leading culture style. An organisation rarely has only one culture type. Time and again, there is a mix of the four organisational cultures.

What does an OCAI show?

Shown as a three-dimensional graph, the survey of the opinion of the OC from the organisation’s leaders and followers, at present, and preferred:

1. The dominant current culture. The example suggests a Hierarchical, but also has significant proportions of the other three sub-cultures.

2. The discrepancy between the present (pink area) and preferred culture. (blue)

3. The strength of the current culture.

4. The congruency of the six features. Cultural incongruence frequently leads to a desire to change, because different values and goals can take a lot of time and debate. Evidence suggests that this organisation wants to move away from hierarchy to adhocracy. They have an appetite for risk and innovation.

5. Evaluation of the culture profile with the average for the sector.

6. Comparison with average tendencies; in what phase of development is the organisation?

As a leader, this data provides the opportunity to grow, be creative and innovative, and empower the team(s).

Conclusions

Organisational culture is not to be considered simply as culture. It is a far bigger topic.

OC can evolve, it is dynamic, not static.

OC is values in action through behaviours.

It is one way of describing the organisation, not the only way, and it can exist (often quite healthily) as sub-cultures, particularly in large organisations with lots of teams/departments).

The environment, including changes in technology, shifting perspectives on the natural environment, greater emphasis on well-being and personal growth, changing workforce capabilities, and customer requirements (to name just a few), can all impact what organisational culture needs to become.

Understanding what it is now requires understanding through education.

Understanding how to change it requires education.

An organisational coach should be knowledgeable and skilled in the contemporary approaches and historical pitfalls of different types of organisational culture.

Gerard McCann

MBA: Coaching, Mentoring, and Leadership.

Commentaires